‘My dream had died’ XTC’s Andy Partridge on mental illness, battling the music industry and losing his muse

‘My dream had died’: XTC’s Andy Partridge on mental illness, battling the music industry and losing his muse

Andy Partridge knew that he would never perform live again as he lay on a stretcher in a Los Angeles emergency room between two gunshot victims. His band XTC did not know it, but they had just played their final show. “My dream had died,” says Partridge, his voice cracking at the memory 40 years on.

It was 1982 and the British group were riding a commercial high off the back of what is still their best-known song, Making Plans for Nigel. But Partridge was suffering. He had been attempting to get off the Valium he had been prescribed aged 12 after his mother was temporarily placed in a mental hospital. “It was the 60s,” he says, summing up the attitude of the time: “‘Poor kid’s upset, his mum’s loopy, why not stick him on Valium?’ I became addicted.”

On a 1981 tour of the US, he had tried to go cold turkey. “Over the next year, my brain melted,” he says. He suffered memory loss and bouts of immobility, and says his repeated warnings to management and label Virgin went unheeded: “I was laying them a golden egg.”

XTC: Senses Working Overtime – video

During a live televised show in Paris, he had a panic attack and afterwards was found backstage in the foetal position. Days later, Partridge boarded a plane to start a US tour. The band should have played a sold-out Hollywood Palladium. Instead, Partridge was rushed to hospital. The cancelled dates would accrue the band eye-watering debt.

Partridge says his retreat from the road became a kind of blessing. “My love of making records came to the fore once I knew they didn’t have to be built for reproduction.” He developed a reputation as a studio wizard, XTC releasing another seven albums before they split in 2006. But today he has stopped writing songs, saying that he has lost “the anger and the fight” with age. When I contacted him to arrange this interview, he was initially reluctant, telling me he has entered his “withdrawal years”.

What does he mean by that? “It’s difficult because it’s just a feeling,” explains Partridge on FaceTime from his home in Swindon, his face augmented by round spectacles. “It’s just ‘getting old’ shit.” He will be 70 next year and has been suffering from a heart condition, as well as the tinnitus that has in the past made him contemplate suicide. There is also the OCD that has persisted since childhood.

The occasion for the interview is My Failed Christmas Career: the latest in a series of archival releases, it documents festive songs that Partridge wrote with the intention of selling to other artists. Other than two songs recorded by the Monkees, the rest never found buyers. Does he enjoy Christmas? “Oh, it’s fabulous,” he says in his lusty West Country burr. “It all comes from paganism.”

He recounts the tale of one “nuclear Christmas Day” 20 years ago. “I thought, I’ll put on a bit of a show for the kids,” says Partridge, who dressed up as Father Christmas to cook for his children and parents. He overindulged on champagne, and ended up unleashing “many, many years of bottled-up anger” on his mother. Bottle in hand, he headed out into the night. “I ended up in a kids’ playground, the earth was wet, and I was just laid on the mud having a kind of primal scream moment.” Local police returned the muddy, tearful Santa to his relieved family.

Partridge was born in Malta in 1953 to a naval family , who settled in a council house in Swindon when he was two. An only child, and with his father absent on navy work for long stretches, he was left alone with the “obsessive OCD” of his mother.

“She treated me like a bit of a dog,” he says, audibly choked up. “Let me just say, I wasn’t wanted.” He remembers going round to a friend’s house and staring transfixed at the Beatles-themed wallpaper. “I went to see A Hard Day’s Night in my duffle coat and shorts,” he recalls, after which he began learning Beatles’ songs on guitar.

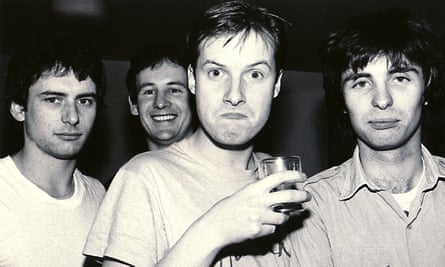

‘Being in a drinking gang that saw the world was thrilling’ … XTC in 1980, (l to r) Terry Chambers, Dave Gregory, Andy Partridge and Colin Moulding. Photograph: Paul Natkin/WireImage

Regularly found sporting green eyeshadow, his mother’s blouses and a 3ft tiger’s tail, Partridge established himself as a small-town maverick. He recruited Colin Moulding on bass and Terry Chambers on drums to his band Star Park; with Barry Andrews on keyboards, in 1975 they became XTC. It was just in time to sign with Virgin as part of the punk explosion, but their nervy eccentricity was closer to Elvis Costello or Talking Heads, with whom they toured in the late 70s.

Despite their similarity to those metropolitan new wave greats – and approval from their US peers – Partridge thinks their small-town origins made British listeners think of them as parochial. “One of the reasons we never clicked in England is because Swindon is the joke town,” says Partridge, who remembers being advised by Virgin to lose his accent. “We said: ‘No, we’re from the West Country, we talk like this, we think like this.’”

Partridge says he struggled to maintain the band as a “benevolent dictatorship”, sacking Andrews in 1978 and inducting the band’s secret weapon, the softly spoken guitarist and arranger Dave Gregory, a year later. Moulding began writing songs and authored the band’s surprise Top 20 hit Making Plans for Nigel. Fearing a loss of control in the wake of its success, Partridge upped his game. By 1980’s Black Sea, XTC had come of age, with two songwriters producing increasingly sophisticated and complex guitar pop. Remarkably, the band recorded their first serious masterpiece, 1982’s The English Settlement, during Partridge’s withdrawal from Valium. “Being in a drinking gang that saw the world was thrilling,” concedes Partridge of those commercial peak years, “but it paled quickly.”

After quitting touring, brilliant records such as 1983’s Mummer tanked commercially. One day, Chambers left rehearsals and never returned. Career salvation, though, came in an unlikely form. In 1985, with leftover studio time from a cancelled production job, XTC recorded a low-budget, affectionate parody of the 1960s psychedelia they had grown up with. Released under the alias the Dukes of Stratosphear, the hoax commercially leapfrogged the most recent XTC releases and bought the band time with Virgin.

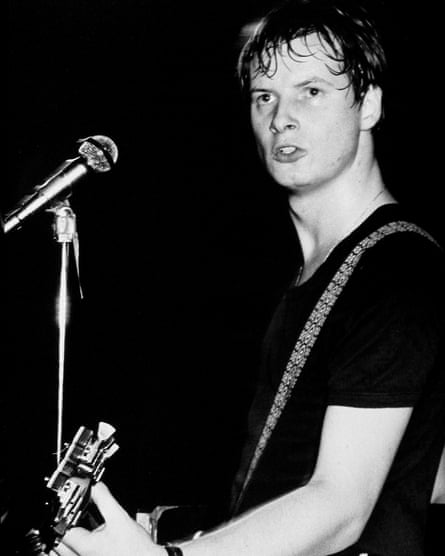

‘I think I’m on the spectrum, yes, but I think it’s all helped me and I wouldn’t have it any other way’ … Partridge on stage, 1979. Photograph: Allstar

“We were becoming widescreen,” says Partridge. “Livid colour.” This was never more so than on 1986’s highly celebrated Skylarking, the volatile sessions for which became the stuff of legend owing to Partridge’s combustible working relationship with producer and US prog legend Todd Rundgren. How bad did it really get? “There may have been an axe in the corner of the room,” Partridge says with a grin, “and I may have said: ‘If you carry on down that road I’ll put that thing through your fucking head.’”

Though XTC’s 1990s began triumphantly with the autumnal, slow-burning Nonsuch album, it would be the most punishing decade of Partridge’s life. When Virgin cancelled the single release of Wrapped in Grey – heavily inspired by the Beach Boys and one of Partridge’s most life-affirming songs – he called his band out on strike.

“We knew that if we recorded anything, [Virgin] would own it,” says Partridge, who remains strident against an industry that “loans you money to make albums that they then own”. Without touring revenues, and only Partridge earning a decent wage from songwriting royalties, the band were skint. He won’t name names, but Partridge says that during a low point of the strike one of the band took to illegally selling petrol by the motorway. He was invited to produce Blur’s second album, the band hoping he would be their George Martin. There was, he recalls, “far too much dope going on” for his tastes, and he was sacked.

Partridge had been married to Marianne Wyborn since 1979, and they had two children. But in 1994, they split and he began a relationship with US film heiress Erica Wexler, who herself was in a relationship with the elderly Roy Lichtenstein. “Rather unfairly,” says Partridge, “I gave her a bit of an ultimatum.” Faced with a choice between two pop-art masters, Wexler has lived in Swindon ever since.

Eventually let go by Virgin, the three-piece XTC plotted their next move: to record an album with a 40-piece orchestra that would put them back on the map. Only the band ran out of cash and could only afford the symphony players for one day. The long-suffering Gregory finally snapped and left. The end result, 1999’s Apple Venus Volume 1, may be their best album, a deep dive into the old weird England of maypoles and harvest festivals. “Nature is just sex and it’s so important to keep hold of all of that,” says Partridge. “You’re talking to an ex-King of the May here.”

Though increasingly infrequent, the heart of later XTC records would always be Moulding’s gentlemanly homilies to quiet living. In 2006, they split over a row about his garden shed studio, an event announced in the Swindon Advertiser. “I’d hate you to think I’m knocking anyone in the band,” says Partridge. “I love them to bits. An only child, I never knew the brother thing, but they were my brothers.”

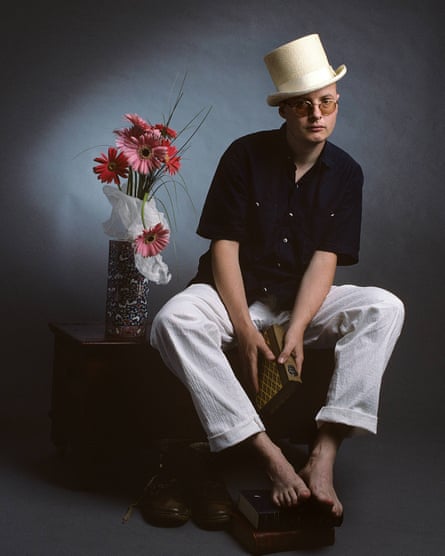

‘I’d hate you to think I’m knocking anyone in the band – I love them to bits’ … Partridge in 1989. Photograph: Ebet Roberts/Redferns

After XTC withdrew to the studio in the early 80s, fans realised that their favourite live act were never going to return and in 1989 held their first fan convention. In September, an old art deco cinema just off Swindon’s high street hosted more than 150 fans gathering to enjoy English Sediment real ale, Bhangra renditions of XTC hits and a charity raffle of hats worn by Partridge during the band’s pomp.

“Being in Swindon is very surreal,” enthused Ashley, who – with best friend Lexie – had travelled from California to the convention in a hand-knitted jumper bearing the sleeve of XTC’s 1979 album Drums and Wires (which opens with Making Plans for Nigel). “It’s almost like they’re the Beatles, but they’re better than the Beatles.”

Partridge, who addressed a rapt conference via video link, is proud of the fanbase, though confesses that the celebration badly triggers his OCD: he stayed firmly upstairs at home that weekend, and has previously hinted that he is autistic. Has he ever sought a formal diagnosis? “I think I’m on the spectrum, yes, but it’s all helped me and I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

Partridge is rarely sighted in his hometown, keeping nocturnal hours and staying at home where he devours military history. His vast collection of toys – mostly soldiers, some he has made himself – cover almost every display surface. Partridge tried social media, but withdrew following allegations that he used antisemitic tropes in a discussion on Middle Eastern politics (something he won’t be drawn on today). He’s given up his chief hobby of arguing with strangers about politics on online forums, telling me he now spends his days “waiting for my music mojo to return, in between researching UFO events”.

He watched with envy and approval recently as a new generation discovered Kate Bush thanks to Stranger Things. “Part of me does long for that Nick Drake moment,” he says, of the folk singer’s resurfacing through a car advert.

As the afternoon comes to an end, I ask Partridge who he feels won in his long battle with the music industry. A pause gives way to a hearty laugh. “Of course I did!” he thunders. “I got a life out of it. They’re not a sculptor, they’re not a painter, they’re not poets. All they’ve got is money. And money’s nothing.”

My Failed Christmas Career is out now on Ape House